According to the ACT approach, experiential avoidance is always at the foundation of the internal obstacles that arise and prevent us from achieving our goals. This is the same for any kind of blockage, including writer’s block. Experiential avoidance in writers results in us behaving in ways that undermine the achievement of our writing goals. The ACT hexaflex is designed to overcome experiential avoidance and increase psychological flexibility through the acquisition of new cognitive and behavioural skills. However, before us writers can overcome obstacles to achieving our writing goals, we need to understand the avoidance strategies we use, albeit not consciously, and become much more aware of how our thoughts, feelings and sensations lead to avoidance behaviour- and even that dreaded writer’s block.

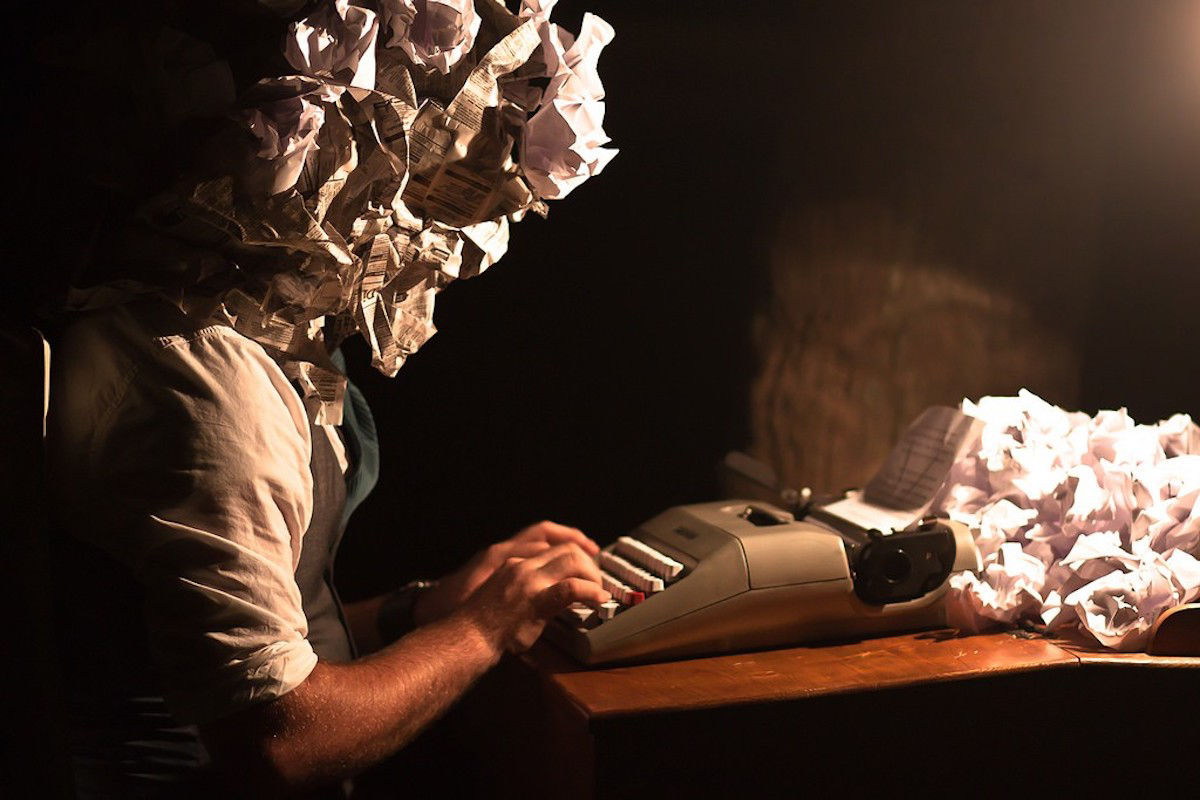

The Focused Flow model approaches writing coaching by establishing values-driven writing goals, and then taking an inventory of obstacles that arise when a writer approaches their writing task. For each person, the obstacles that arise will be unique. Yet there are some common problems that many writers face when they approach a writing task. One is procrastination, which tends to be driven by overthinking the writing task, leading to uncomfortable sensations or feelings and the perpetual delay of writing to avoid this discomfort. When faced with a blank screen or page, many experience overwhelm due to overthinking the task ahead which puts the brake on the writing process. Procrastination helps writers to avoid this common experience of writer’s overwhelm. From an ACT perspective, Russ Harris calls this behaviour an ‘away move’ because procrastination diverts us away from the achievement of our goals.

I have noticed that before I sit down to write about any aspect of the writing process, I seem to experience the very problem I’m thinking of writing about. For example, today, I intended to write a blog post about experiential avoidance- and I finally started writing about it after 5pm, but not before cleaning my apartment, sorting out the laundry, ordering my food shopping, taking out the trash, giving myself a facial, and looking at various freelance writing and editing opportunities to boost my income across about twenty websites. This resulted in a growing sense of agitation and even dread. I was aware I was avoiding today’s writing goal, yet there I was, saying I could coach others to achieve theirs! Cue the emergence of the internal critic in full self-condemnation and judgement mode… ‘you haven’t got what it takes, you’re out of your depth, you should stick to editing, who’s going to take you seriously? Why would anybody part with their hard-earned money to learn from somebody like you?’ And so on and so on… which is my version of what ACT practitioners term the ‘I’m not good enough story’.

So, I connected to that experience, and became aware I was feeling uncomfortable and agitated. I connected to the sensations in my body- a kind of dread in the pit of my stomach, a heaviness in my heart that I associate with disappointment, not about a cancelled event, but disappointment with myself. I realised I was at what Russ Harris calls ‘the choice point’, like a fork in the road, with one path taking me away from my writing goals- by going for a walk, having a glass of wine, or finding some other task such as doing a tiny bit of washing up that could easily wait. My ‘I’m not good enough story’ was kicking off along with all the uncomfortable feelings that accompany it, and I had to choose whether to get hooked into the story or remain aware of my uncomfortable feelings, sit down, and just start writing instead. This short video illustrates ‘the choice point’ visually.

I became aware I was at my choice point by connecting to the present moment and noticing my thoughts, feelings, sensations and the urge to indulge in further procrastination, more avoidance and ‘away moves’. According to the ACT model, this dropping into awareness and connecting to the present moment is termed ‘mindfulness’. By becoming more mindful, I was able to choose a ‘towards move’ while remaining aware of my discomfort, picking up my laptop, sitting down and starting to type.

Next, during the writing process, I remembered the problems I’d encountered with potential coaching clients who’d queried the use of mindfulness as a solution to overcoming obstacles to writing. So much so, that I’d been careful to remove the term ‘mindfulness’ from my promotional material and website pages. Then, my mind began to comment negatively on my use of the term mindfulness. The reason? Almost all my potential clients were put off by the idea of having to meditate in order to write! They had associated mindfulness with meditation. I was surprised, but then I’ve been an ACT practitioner for eleven years and had chosen to practice ACT as a coach because it doesn’t involve meditation! I’d previously trained in other mindfulness-based therapies- MBCT and MBSR -which do require a regular meditation practice. This requirement led to problems for some of my peers who found making time to meditate difficult, and had undermined their progress with the approach. Then, along came ACT- a mindfulness-based active coaching approach that required no meditation- so I jumped into further training then began using it with a lot of success, especially with writers in my retreat house in Sri Lanka.

So, I decided to ignore my mind telling me it was a bad idea to discuss mindfulness in this article about the writing process. There are several myths about mindfulness, but instead of avoiding using the term I decided it’s time to do some myth busting instead. Take a look at the short video below by the ACT coach Russ Harris.

Thanks to my mindfulness skills, I was able to choose to behave in a way that achieved today’s writing goal, despite all the uncomfortable thoughts and feelings that arose when I thought about sitting down to write. In addition to connecting to the present moment and noticing the thoughts, feelings and sensations driving my procrastination, I decided to let them be there and unhooked from the impulse to avoid them. In the ACT hexaflex model, these further skills in mindfulness are termed ‘acceptance’ (allowing uncomfortable aspects of our experience to just be there) and cognitive defusion (unhooking or refusing to ‘fuse’ with the ‘I’m not good enough story’).

The next post will discuss these additional mindfulness skills in detail. Acceptance and cognitive defusion enable us to choose ‘towards moves’ by making space for us to enter the flow state, maintain our focus, and achieve our writing goals. Thankfully, mindfulness helped me achieve my writing goal today, otherwise you wouldn’t be reading this post now! If you like my investigation of the writing process, please click and subscribe in the sidebar to receive notifications by email. My posts will be full of tips and techniques to help overcome obstacles to all types of writing in the coming weeks ahead.